The times that we inhabit are a clear-cut demarcation of territorial and regimental operations. It is these lines, sometimes invisible and sometimes made distinctly visible and at times deliberately blurred that announce the subject position and subjecthood of an entity. Not just a living existence but also the ‘other’ that makes us aware of power. It is the association with the land, asserting a claim over it for survival and the forceful evacuation and its exploitation in the guise of the narrative of ‘progress’. While modernity can be a tool and a hope for certain communities to claim their personhood, its operations function in the chaotic field of power. Nation formation, a crucial field of power, interpellates individuals as citizen subjects. A force that governs all and everything in its jurisdiction. Thriving of aesthetics in this context is a question of ethics that cannot be negotiated. By substituting the subject in the compound designate of citizen subject, we may derive the category of the citizen artist whose ethics becomes prescient in the aesthetic bind[1]. In the flux of giving and choosing, in this case, a

citizen artist, this opportunity is to dwell in the practice of artist, environmentalist, curator, and writer – Ravi Agarwal.

As rich and diverse as the Indian subcontinent is in its biodiversity and ecological landscapes, so have its socio- cultural functioning that is inscribed in caste hierarchies, religious practices, and gender differences; these factors are directly interconnected with the aspects of ecology, within the broader construct of nature. India’s long history of people’s struggles is intertwined with the socio-cultural and economic relationship with the natural world. The Chipko Movement (the 1970s, women saving forests from tree logging), the Narmada Bachao Andolan (1980s to now, against big dams and displacement), the Bhopal tragedy struggle (since 1984, for environmental justice from large multinationals), or the Niyamgiri movement (2000s, saving a sacred hill from being mined for bauxite)

are but a few that demonstrate how the ideas people have of their futures could be different from those driving modern development processes, which do not factor in complex relationships with nature [2].

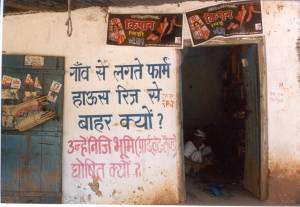

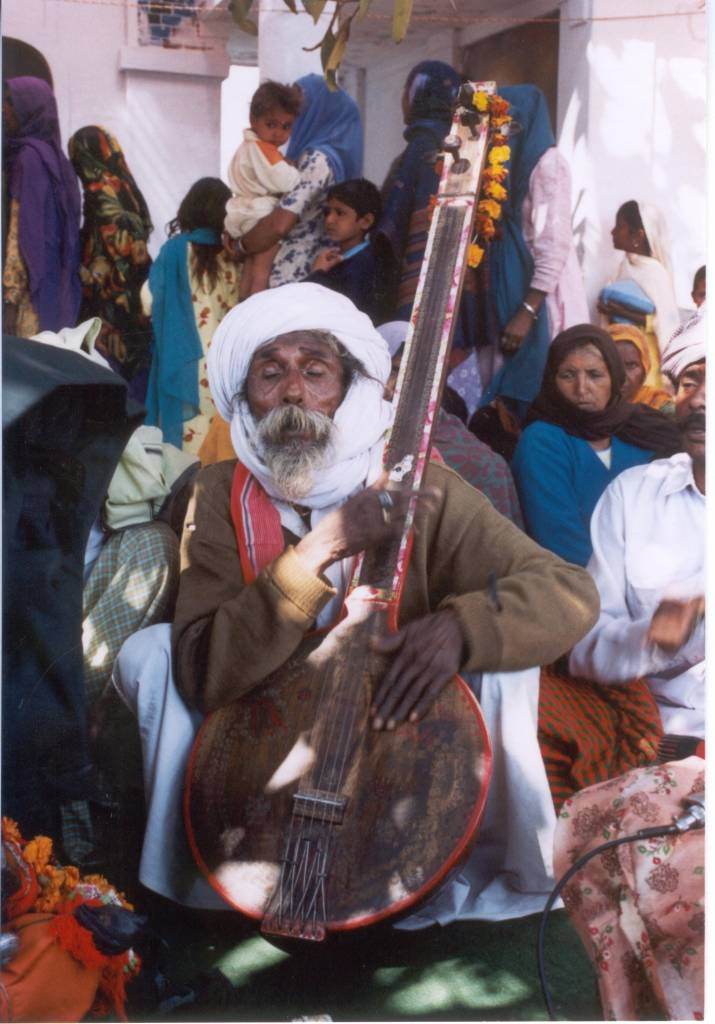

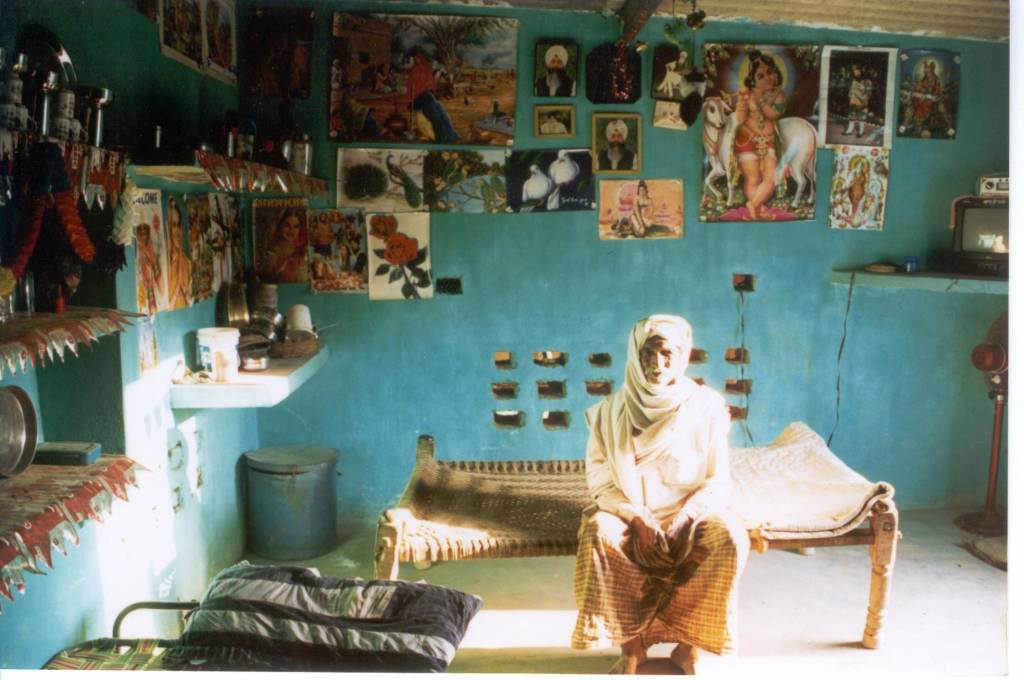

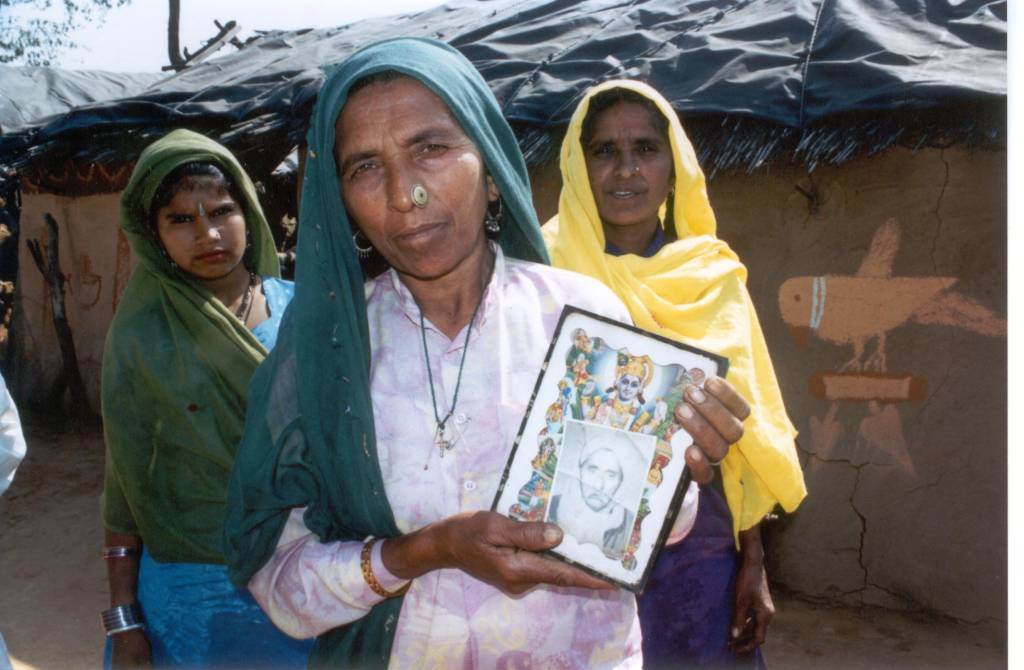

Ravi’s work Bhatti Mines (2004), is a photographic engagement with the Odhs, a Hindu community, who migrated from Pakistan during the partition and settled in the region in the early 1970s. The Odhs primary occupation is connected with mud

which consists of digging mud and are earth masons. Bhatti mines are a huge complex of quarries that for 25 years yielded red sand, silica, and stone for Delhi’s construction industry. Closing down in the 90s, the land was converted into a national park making the people homeless. Known for burying their dead, they now need to seek permission to visit their ancestral graves.

In this work Ravi has observed the displacement of a community, documenting altering realities and

asking for responsive actions. People and human geography have always been an intrinsic part of his practice, that significantly aligns with environmental concerns. Ravi aspires to an imagined homeland of the future and raises concerns that our time is facing and experiencing. His practice is rooted in action, creative processes in observation, and being a witness and responsive to ecological and socio-political conditions. His works compel individuals to look in a particular way

and build a way of seeing which is conscious, receptive, and critical.

[1] Kapur, Geeta; Aesthetic Bind: Citizen Artists: forms of address

https://criticalcollective.in/ArtistInner2.aspx?Aid=166&Eid=97

[2] Agarwal, Ravi; State of Nature in India: An Essay

https://www.raviagarwal.com/2021/08/10/state-of-nature-in-india-an-essay/

[3] Picture Credits: Ravi Agarwal