‘Art is a reflection of life. Life isn’t something we can cut and fix. It’s always in a state of flux’

– El Anatsui

From the 1940s to the 60s, the African countries were experiencing a cultural renaissance based on the values of liberation and decolonization. A student of art education in Kumasi, Ghana somehow felt the alienating approach of art that surrounded the African art education ecosystem, majorly based on Western principles. The growing up of that student was in conflicting communication with the broader context of African art, which has been marginalized in the global art narrative so far. Traditional African art, often seen through the lens of ethnography rather than as high art, is rich with symbolism, functionality, and cultural significance. The giants of 20th-century paintings like Picasso and Matisse were heavily influenced by West African art and symbolism.

El Anatsui, the then student of art education in Kumasi visited the National Cultural Center in Kumasi to observe the local artists working in various mediums ranging from bronze, and brass to printed textiles and over here, he first encountered ‘Adinkra’- a system of visual signs and symbols as a portal to his first introduction of abstract art. Gradually, the boy understood the galaxy of visual art found and originated from his continent and a new perspective, non-conforming to the boundaries imposed by Western art history.

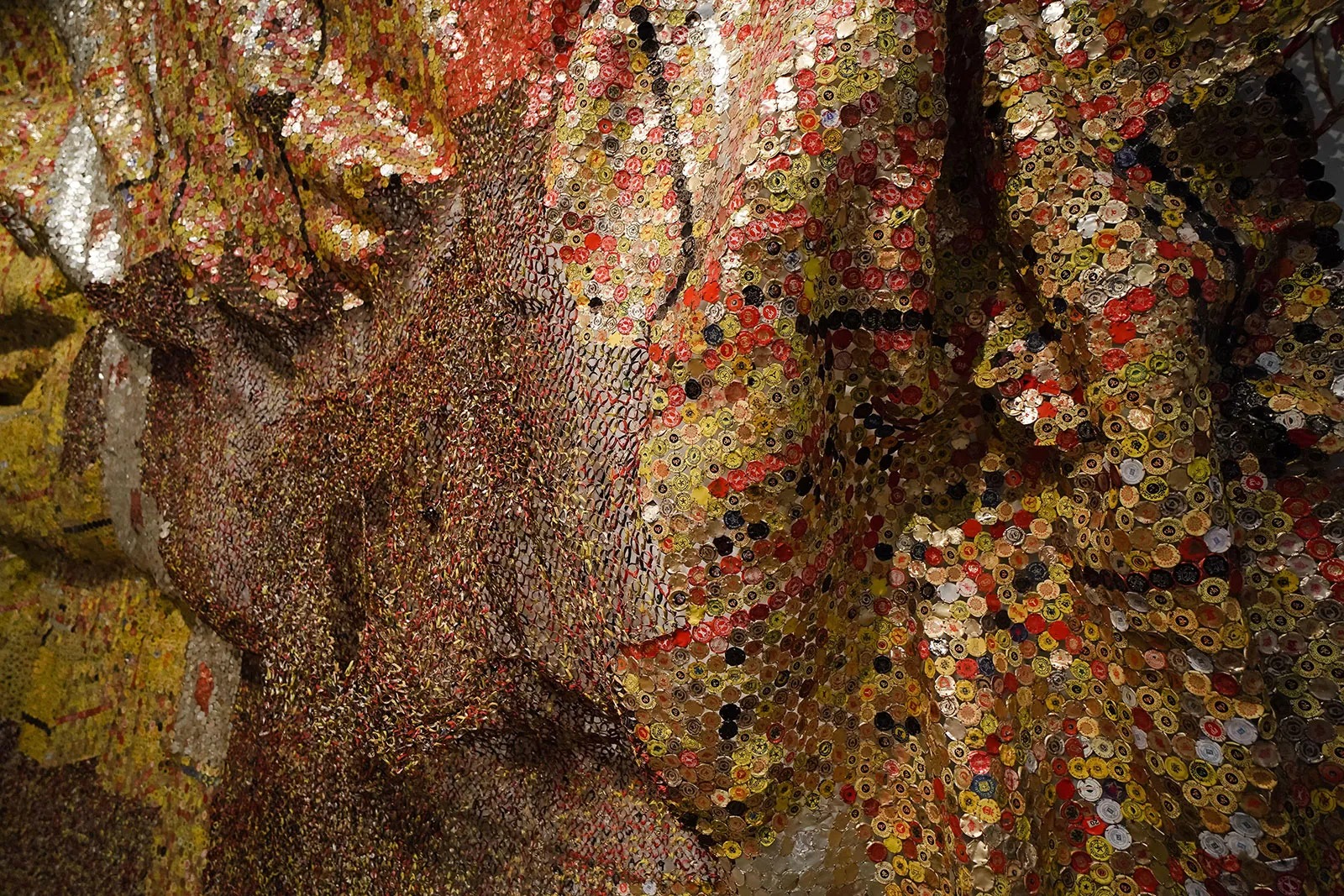

Anatsui is founded on the belief that art is a dialogue between materials, culture, and the environment. He is well-known for his ability to turn ordinary and discarded materials into elegant, large-scale works that prompt spectators to contemplate the meanings and histories contained in common things. Over a 50-year career, he worked in a variety of materials, including wooden pallets, clay, and bottle tops. His works frequently combine found objects such as bottle caps, metal strips, milk-tin lids, and other scraps, which he skillfully weaves together to create shimmering tapestries that blur the distinction between sculpture and textile art.

Anatsui’s work contains several themes, including the destruction and subsequent reconstitution of material as a metaphor for life and the changes that Africa experienced during colonialism and since independence; traditional themes and motifs of West African strip woven cloth and other African textiles; and concern about Western scholarly misinterpretation of African history and the distortions it has caused. His art is also thematically related to the West African cultural environment and concepts of consumerism and labor.

Anatsui’s art is greatly influenced by traditional African aesthetics and rituals. He is inspired by the Kente fabrics of Ghana and the Uli designs by the Igbo people of Nigeria, among other cultural objects. Anatsui raises concerns about consumerism, waste, and material transformation while simultaneously honoring African cultures’ resilience and ingenuity.

With the observation and playfulness of a child and a scholarly interest, he is interested in presenting, seeing, and transforming materials that resonate with history. The artist says-

“When something has been used, there is a certain charge, a certain energy, that has to do with the people who have touched it and used it and sometimes abused it. This helps to direct what one is doing, and also to root what one is doing in the environment and the culture.’’

Anatsui’s art also incorporates the concept of Sankofa (going back and retrieving). He sees it as a method of drawing on the past and the lessons it teaches to map a path forward. Sankofa described a need to draw from what was immediately around him; Ghana gained independence when he was in high school, and much of his education had been focused on Western art and art history, so he felt called to ‘go back and retrieve’ suppressed aspects of the Ghanaian culture, which he described as a ‘quest for self-discovery’.

El Anatsui offers a completely new meaning inside his work by weaving together abandoned and ejected materials, in the abstract language of art that demands no words. From the start, he seized control of his creative vision, rejecting any imposed boundaries or restraints on his creativity that determined what art should or should be, disputing the notion that art can only be done right in the West.

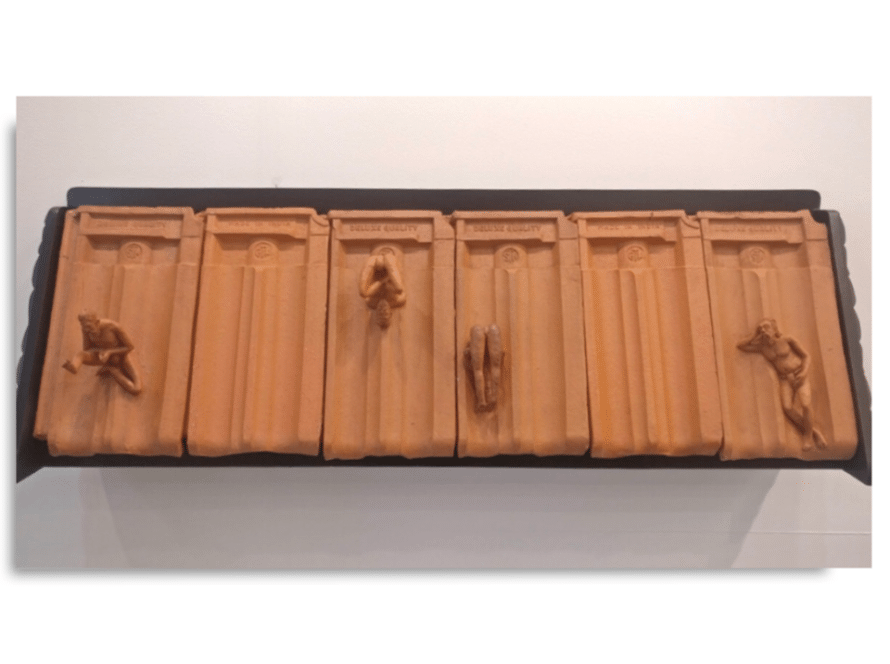

Anatsui started making three-dimensional works much before his well-known bottle cap tapestries. His early pieces were created using wooden trays obtained in Anyako marketplaces. In the 1970s, in Nsukka, he made ceramic works out of clay and manganese. In the 1980s, he created sculptural works using concrete and terrazzo, some of which could still be found on the Nsukka campus. His hardwood works gained popularity, and his influence grew.

Anatsui shifted to Nsukka, Nigeria in 1975 and then decided to stay, being attracted to Nigeria from the first for the likes of cultural icon Fela Kuti and people alike. Now, by the local community, he is honored with the chieftaincy title of Ikedire of the Ihe-Nsukka kingdom.

The artist is famously known for his work with bottle caps where he builds structures of an ephemeral gossamer-esque sheet which are visually striking, characterized by their shimmering, tapestry-like appearance. In the late 90s, while working as a professor in Nigeria and walking by the street, he noticed a bag of discarded bottle caps which he took back to his studio. In his words- it was like an invitation and the material itself led him to the work. By cutting the bottle caps, sourced from local liquor distilleries, Anatsui and his team of assistants create the composition by attaching the caps with copper wires in multiples. The colors and textures of the caps create dynamic, mosaic-like surfaces that shift and change with the light and the viewer’s perspective. The large-scale nature of the installations often evokes the grandeur of traditional textiles, while their flexibility and fluidity allow for organic, flowing forms.

Illustrating the history and functions of objects, Anatsui dwells in historical storytelling. With the bottle caps, the history of the transatlantic trade and slave trade is embedded; the Africans were sent to America to produce rum and other things, which came back to Europe and finally to Africa. The bottle caps are objects linking three continents of history here.

Interested in the flow state of a sculptural object, Anatsui often surprises the receivers of his works while sending them in an innovative form like folding them in a small crate or briefcase. Stating his works as ‘Unfixed Forms’ he often leaves the galleries and curators to decide how to display his works.

Anatsui’s installation “Fresh and Fading Memories” at the 52nd Venice Biennale was a pivotal moment in his career. Robert Storr, curator of the 2007 Venice Biennale, credits him with renewing abstraction’s depleted emotional force, creating a formal language in which tragedy and sublimity are newly convincing. In the last year, El Anatsui’s work ‘Behind the Red Moon’ opened at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, the work is a staged visual experience in three acts, a monumental sculptural installation primarily made of thousands of metal bottle tops.

In a time of climate crisis, Anatsui’s work has become increasingly relevant through his sustainable sourcing of materials and his repurposing of found objects often discarded as waste.

El Anatsui’s influence extends beyond the art industry; he is a deep humanitarian whose work explores universal themes like change, resilience, and the interconnectivity of human lives. His work has encouraged a new generation of African artists to investigate and express their cultural identities in novel ways.

El Anatsui’s works are striking illustrations of how art can be used to promote social and environmental sustainability. Anatsui’s imaginative use of waste materials, celebration of cultural history, and involvement with societal concerns have all proved art’s transformational power.

El Anatsui’s life and work are a testament to the power of art to transcend boundaries and transform perceptions. Through his innovative use of materials and his deep engagement with African cultural heritage, Anatsui has made an indelible mark on the art world. His legacy is one of creativity, resilience, and a profound commitment to exploring the human condition through the lens of individual and collective experiences.

The photographs’ copyright belongs to El Anatsui